1. Introduction to Photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is a light-driven process in which a catalyst accelerates a chemical reaction without being consumed. The term is derived from the Greek words photo (light) and catalyst (one that speeds up reactions). In photocatalytic systems, light energy—typically ultraviolet (UV), visible, or near-infrared radiation—is absorbed by a photocatalyst, generating reactive species capable of driving chemical transformations.

Photocatalysis has attracted significant attention due to its potential to address global challenges such as environmental pollution, energy shortages, water purification, and sustainable chemical synthesis. It is considered a green technology because it often operates under ambient conditions, uses solar energy, and minimizes harmful by-products.

2. Historical Development of Photocatalysis

The concept of photocatalysis dates back to the early 20th century, but major advancements occurred in 1972 when Fujishima and Honda demonstrated the photoelectrochemical splitting of water using a titanium dioxide (TiO₂) electrode. This discovery laid the foundation for modern photocatalysis research.

Since then, extensive research has focused on improving photocatalyst efficiency, expanding light absorption into the visible region, and developing practical applications in environmental remediation and renewable energy.

3. Fundamental Principles of Photocatalysis

3.1 Role of the Photocatalyst

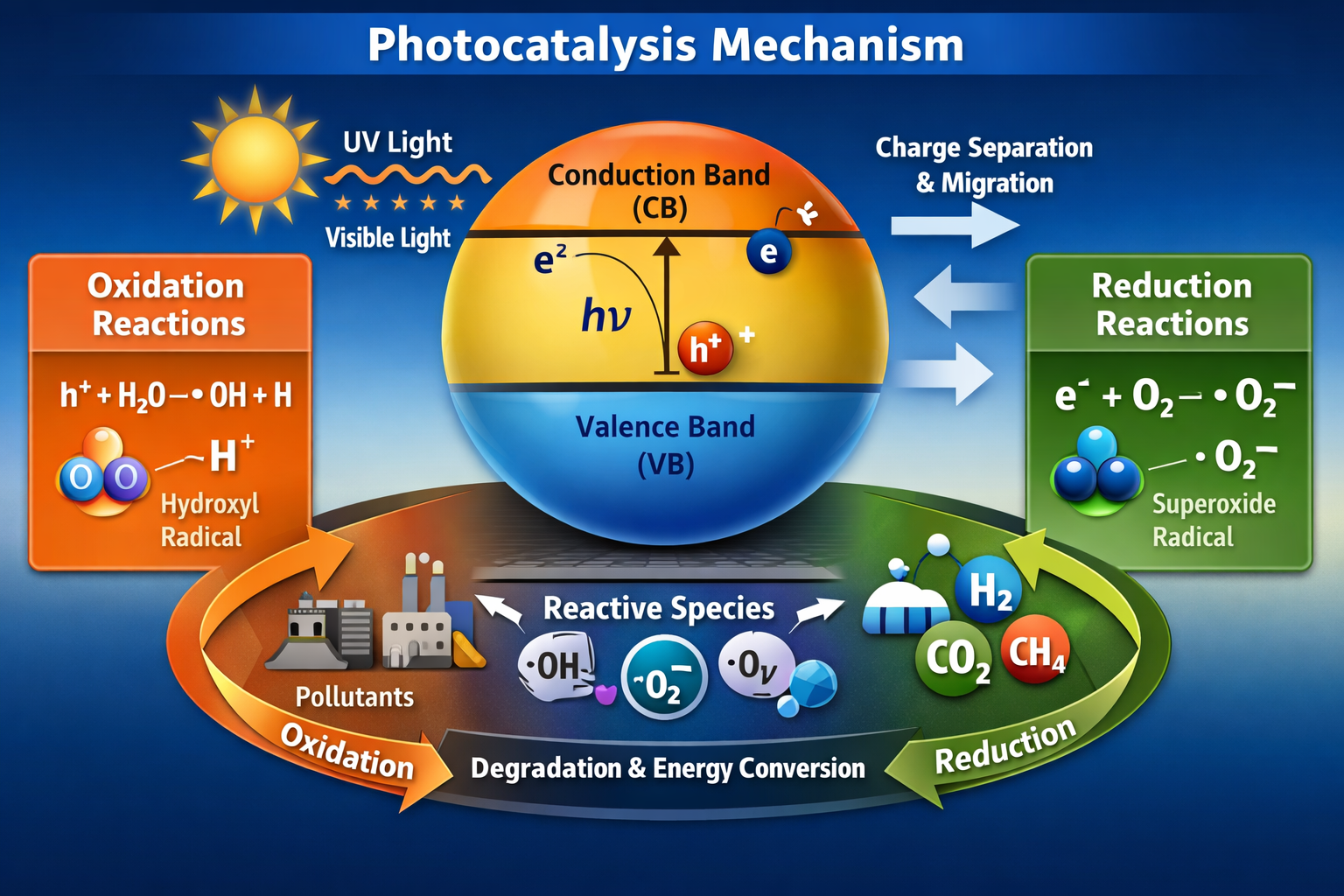

A photocatalyst is typically a semiconductor material such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), cadmium sulfide (CdS), or graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄). These materials possess a valence band (VB) and a conduction band (CB) separated by a band gap.

The band gap determines the wavelength of light the material can absorb. For example, TiO₂ has a wide band gap (~3.2 eV), meaning it primarily absorbs UV light.

3.2 Light Absorption and Charge Generation

When a photocatalyst absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap, electrons are excited from the valence band to the conduction band. This excitation leaves behind positively charged holes in the valence band. These photogenerated electrons and holes are responsible for initiating redox reactions on the catalyst surface.

3.3 Charge Separation and Migration

For efficient photocatalysis, the generated electrons and holes must be separated and transported to the surface before recombining. Recombination releases energy as heat or light and reduces photocatalytic efficiency.

Various strategies such as doping, heterojunction formation, and surface modification are employed to enhance charge separation and prolong charge carrier lifetimes.

4. Photocatalytic Reaction Mechanism

4.1 Oxidation Reactions

Photogenerated holes are strong oxidizing agents. They can react with water or hydroxide ions to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which are highly reactive and capable of degrading organic pollutants.

4.2 Reduction Reactions

Photogenerated electrons in the conduction band participate in reduction reactions. For example, electrons can reduce dissolved oxygen to form superoxide radicals .These reactive oxygen species play a crucial role in pollutant degradation and antimicrobial activity.

5. Types of Photocatalysis

5.1 Homogeneous Photocatalysis

In homogeneous photocatalysis, the photocatalyst and reactants exist in the same phase, usually liquid. Although reaction rates can be high, separation and reuse of the catalyst are challenging.

5.2 Heterogeneous Photocatalysis

Heterogeneous photocatalysis involves a solid photocatalyst and reactants in a liquid or gas phase. This is the most widely studied type due to easy catalyst recovery and stability.

6. Photocatalytic Materials

6.1 Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

- Titanium dioxide (TiO₂)

- Zinc oxide (ZnO)

- Tungsten oxide (WO₃)

These materials are stable, non-toxic, and inexpensive but often limited by UV-only activation.

6.2 Sulfide and Nitride Photocatalysts

- Cadmium sulfide (CdS)

- Zinc sulfide (ZnS)

- Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄)

These materials absorb visible light but may suffer from photocorrosion or lower stability.

6.3 Composite and Doped Photocatalysts

Doping with metals or non-metals and forming composites with graphene or noble metals enhances visible-light activity and charge separation.

7. Applications of Photocatalysis

7.1 Environmental Remediation

Photocatalysis is widely used for degrading organic pollutants such as dyes, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). It can mineralize pollutants into harmless end products like CO₂ and H₂O.

7.2 Water and Wastewater Treatment

Photocatalytic processes are effective in removing bacteria, viruses, and organic contaminants from water. Photocatalytic disinfection offers an alternative to chemical disinfectants without producing toxic by-products.

7.3 Air Purification

Photocatalytic coatings on building materials can decompose air pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), sulfur compounds, and airborne microorganisms under sunlight.

7.4 Hydrogen Production via Water Splitting

Photocatalysis enables sustainable hydrogen production by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using solar energy. This process offers a clean fuel pathway with zero carbon emissions.

7.5 Carbon Dioxide Reduction

Photocatalytic reduction of CO₂ converts greenhouse gas into useful fuels such as methane, methanol, or carbon monoxide, contributing to carbon neutrality.

7.6 Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Surfaces

Photocatalytic materials are used in self-cleaning glass, tiles, and textiles. These surfaces decompose organic dirt and inhibit microbial growth when exposed to light.

8. Advantages of Photocatalysis

- Utilizes renewable solar energy

- Operates under mild conditions

- Reduces harmful chemical usage

- Capable of complete mineralization of pollutants

- Environmentally friendly and sustainable

9. Challenges and Limitations

Despite its potential, photocatalysis faces several challenges:

- Low quantum efficiency

- Limited visible-light absorption

- Charge carrier recombination

- Catalyst deactivation and stability issues

- Scale-up and economic feasibility

10. Future Perspectives

Future research focuses on developing highly efficient visible-light photocatalysts, integrating photocatalysis with other treatment technologies, and designing scalable reactors. Advances in nanotechnology, material science, and artificial intelligence are expected to accelerate photocatalyst discovery and optimization.

11. Conclusion

Photocatalysis is a powerful and versatile technology with wide-ranging applications in environmental protection, renewable energy, and material science. Although challenges remain, continued research and innovation are paving the way for its practical implementation on an industrial scale. With growing emphasis on sustainability and green chemistry, photocatalysis is poised to play a critical role in shaping a cleaner and more sustainable future.

you may also visit: Infory